Id, ego, and super-ego

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

|

Concepts

Psychosexual development

Psychosocial development |

|

Important figures

Alfred Adler

Michael Balint |

|

Important works

The Interpretation of Dreams

Beyond the Pleasure Principle Civilization and Its Discontents |

|

Schools of thought

Self psychology

Lacanian |

| Psychology portal |

Id, ego, and super-ego are the three parts of the psychic apparatus defined in Sigmund Freud's structural model of the psyche; they are the three theoretical constructs in terms of whose activity and interaction mental life is described. According to this model of the psyche, the id is the set of uncoordinated instinctual trends; the ego is the organised, realistic part; and the super-ego plays the critical and moralising role." [1]

Even though the model is "structural" and makes reference to an "apparatus", the id, ego, and super-ego are functions of the mind rather than parts of the brain and do not necessarily correspond one-to-one with actual somatic structures of the kind dealt with by neuroscience.

The concepts themselves arose at a late stage in the development of Freud's thought: the structural model was first discussed in his 1920 essay "Beyond the Pleasure Principle" and was formalised and elaborated upon three years later in his "The Ego and the Id". Freud's proposal was influenced by the ambiguity of the term "unconscious" and its many conflicting uses.

The terms "id," "ego," and "super-ego" are not Freud's own. They are latinisations by his translator James Strachey. Freud himself wrote of "das Es," "das Ich," and "das Über-Ich"—respectively, "the It," "the I," and the "Over-I" (or "Upper-I"); thus to the German reader, Freud's original terms are more or less self-explanatory. Freud borrowed the term "das Es" from Georg Groddeck, a German physician to whose unconventional ideas Freud was much attracted (Groddeck's translators render the term in English as "the It").[2]

Contents |

Id

The id comprises the unorganised part of the personality structure that contains the basic drives. The id acts according to the "pleasure principle", seeking to avoid pain or unpleasure aroused by increases in instinctual tension.[3]

The id is unconscious by definition. In Freud's formulation,

| “ | It is the dark, inaccessible part of our personality, what little we know of it we have learnt from our study of the dream-work and of the construction of neurotic symptoms, and most of this is of a negative character and can be described only as a contrast to the ego. We all approach the id with analogies: we call it a chaos, a cauldron full of seething excitations... It is filled with energy reaching it from the instincts, but it has no organisation, produces no collective will, but only a striving to bring about the satisfaction of the instinctual needs subject to the observance of the pleasure principle.

[Freud, New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1933)] |

” |

Developmentally, the id is anterior to the ego; i.e. the psychic apparatus begins, at birth, as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured ego. Thus, the id:

| “ | contains everything that is inherited, that is present at birth, is laid down in the constitution -- above all, therefore, the instincts, which originate from the somatic organisation, and which find a first psychical expression here (in the id) in forms unknown to us" [4]. | ” |

The mind of a newborn child is regarded as completely "id-ridden", in the sense that it is a mass of instinctive drives and impulses, and needs immediate satisfaction. This view equates a newborn child with an id-ridden individual—often humorously—with this analogy: an alimentary tract with no sense of responsibility at either end.

The id is responsible for our basic drives such as food, water, sex, and basic impulses. It is amoral and selfish, ruled by the pleasure–pain principle; it is without a sense of time, completely illogical, primarily sexual, infantile in its emotional development, and is not able to take "no" for an answer. It is regarded as the reservoir of the libido or "instinctive drive to create".

Freud divided the id's drives and instincts into two categories: life and death instincts—the latter not so usually regarded because Freud thought of it later in his lifetime. Life instincts (Eros) are those that are crucial to pleasurable survival, such as eating and copulation. Death instincts, (Thanatos) as stated by Freud, is our unconscious wish to die, as death puts an end to the everyday struggles for happiness and survival. Freud noticed the death instinct in our desire for peace and attempts to escape reality through fiction, media, and drugs. It also indirectly represents itself through aggression.

Ego

The Ego acts according to the reality principle; i.e. it seeks to please the id’s drive in realistic ways that will benefit in the long term rather than bringing grief.[5]

The Ego comprises that organised part of the personality structure that includes defensive, perceptual, intellectual-cognitive, and executive functions. Conscious awareness resides in the ego, although not all of the operations of the ego are conscious. The ego separates what is real. It helps us to organise our thoughts and make sense of them and the world around us.[1]

According to Freud,

| “ | ...The ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world ... The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions ... in its relation to the id it is like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with his own strength, while the ego uses borrowed forces [Freud, The Ego and the Id (1923)] | ” |

In Freud's theory, the ego mediates among the id, the super-ego and the external world. Its task is to find a balance between primitive drives and reality (the Ego devoid of morality at this level) while satisfying the id and super-ego. Its main concern is with the individual's safety and allows some of the id's desires to be expressed, but only when consequences of these actions are marginal. Ego defense mechanisms are often used by the ego when id behavior conflicts with reality and either society's morals, norms, and taboos or the individual's expectations as a result of the internalisation of these morals, norms, and their taboos.

The word ego is taken directly from Latin, where it is the nominative of the first person singular personal pronoun and is translated as "I myself" to express emphasis. The Latin term ego is used in English to translate Freud's German term Das Ich, which literally means "the I".

Ego development is known as the development of multiple processes, cognitive function, defenses, and interpersonal skills or to early adolescence when ego processes are emerged.[5]

In modern English, ego has many meanings. It could mean one’s self-esteem, an inflated sense of self-worth, or in philosophical terms, one’s self. However, according to Freud, the ego is the part of the mind that contains the consciousness. Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean a sense of self, but later revised it to mean a set of psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality-testing, control, planning, defense, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory.[1]

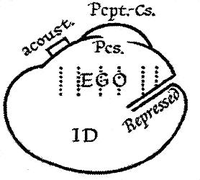

In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted to be half in the consciousness, while a quarter is in the preconscious and the other quarter lies in the unconscious.

When the ego is personified, it is like a slave to three harsh masters: the id, the super-ego, and the external world. It has to do its best to suit all three, thus is constantly feeling hemmed by the danger of causing discontent on two other sides. It is said, however, that the ego seems to be more loyal to the id, preferring to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the super-ego is constantly watching every one of the ego's moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority. To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. The defense mechanisms are not done so directly or consciously. They lessen the tension by covering up our impulses that are threatening.[6]

Denial, displacement, intellectualisation, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalisation, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. However, his daughter Anna Freud clarified and identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealisation, identification, introjection, inversion, somatisation, splitting, and substitution.

Super-ego

The Super-ego aims for perfection[6]. It comprises that organised part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual's ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency (commonly called "conscience") that criticises and prohibits his or her drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions.

| “ | The Super-ego can be thought of as a type of conscience that punishes misbehavior with feelings of guilt. For example: having extra-marital affairs.[7] | ” |

The Super-ego works in contradiction to the id. The Super-ego strives to act in a socially appropriate manner, whereas the id just wants instant self-gratification. The Super-ego controls our sense of right and wrong and guilt. It helps us fit into society by getting us to act in socially acceptable ways.[1]

The Super-ego's demands oppose the id’s, so the ego has a hard time in reconciling the two.[6] Freud's theory implies that the super-ego is a symbolic internalisation of the father figure and cultural regulations. The super-ego tends to stand in opposition to the desires of the id because of their conflicting objectives, and its aggressiveness towards the ego. The super-ego acts as the conscience, maintaining our sense of morality and proscription from taboos. The super-ego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex.[8] Its formation takes place during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex and is formed by an identification with and internalisation of the father figure after the little boy cannot successfully hold the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration.

The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on — in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt (The Ego and the Id, 1923).

In Sigmund Freud's work Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) he also discusses the concept of a "cultural super-ego". The concept of super-ego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its perceived sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore form a weak super-ego, leaving them susceptible to immorality and sexual identity complications.

Advantages of the structural model

The partition of the psyche defined in the structural model is one that "cuts across" the topographical model's partition of "conscious vs. unconscious". Its value lies in the increased degree of diversification: although the id is unconscious by definition, the ego and the super-ego are both partly conscious and partly unconscious. What is more, with this new model Freud achieved a more systematic classification of mental disorder than had been available previously:

| “ | "Transference neuroses correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; narcissistic neuroses, to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and psychoses, to one between the ego and the external world"

- [Freud, "Neurosis and Psychosis" (1923)]. |

” |

Notable appearances in popular culture

- In the 1956 movie Forbidden Planet, the destructive forces at large on the planet Altair IV are finally revealed to be "monsters from the id" -- destructive psychological urges unleashed upon the outside world through the operation of the Krells' 'mind-materialisation machine'.

-In the WiiWare game BIT.TRIP VOID (link: Bit.Trip), the three levels in the game are ID, EGO, and SUPER-EGO. Relating to that, in the cutscenes, apparently Commander Video turns evil or insane.

-In 1998 Squaresoft Game Xenogears, the main protagonist Fei Fong Wong occurs a dis-associative multiple personality disorder with the principles of id, ego, and superego. The Id character inside him is developed due to hidden exterior damage to his spirit and separated, thus becomes a destructive, violent, and full of hatred. Meanwhile his true personality become the super ego which lock himself inside a "shell". Because of this, Fei developed a third ego-like personality that becomes powerless when Id takes over his physical body and gets into rampage, such as destroying his home village Lahan.[9]

See also

People:

|

|

|

Related topics:

|

|

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Snowden, Ruth (2006). Teach Yourself Freud. McGraw-Hill. pp. 105–107. ISBN 9780071472746.

- ↑ Groddeck, Georg (1928). "The Book of the It". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease (49).

- ↑ Rycroft, Charles (1968). A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. Basic Books.

- ↑ Freud, An Outline of Psycho-analysis (1940)]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Noam, Gil G.; Hauser, Stuart T.; Santostefano, Sebastiano; Garrison, William; Jacobson, Alan M.; Powers, Sally I.; Mead, Merrill (February 1984). "Ego Development and Psychopathology: A Study of Hospitalized Adolescents". Child Development (Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the Society for Research in Child Development) 55 (1): 189–194.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Meyers, David G. (2007). "Module 44 The Psychoanalytic Perspective". Psychology Eighth Edition in Modules. Worth Publishers. ISBN 9780716779278.

- ↑ Reber, Arthur S. (1985). The Penguin dictionary of psychology. Viking Press. ISBN 9780670801367.

- ↑ Sédat, Jacques (2000). "Freud". Collection Synthèse (Armand Colin) 109. ISBN 9782200219970, 1590510062.

- ↑ (1998) Xenogears-Perfect Works. DigiCube. page 163-164

Further reading

- Freud, Sigmund (1910), "The Origin and Development of Psychoanalysis", American Journal of Psychology 21(2), 196–218.

- Freud, Sigmund (1920), Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

- Freud, Sigmund (1923), Das Ich und das Es, Internationaler Psycho-analytischer Verlag, Leipzig, Vienna, and Zurich. English translation, The Ego and the Id, Joan Riviere (trans.), Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-analysis, London, UK, 1927. Revised for The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, James Strachey (ed.), W.W. Norton and Company, New York, NY, 1961.

- Freud, Sigmund (1923), "Neurosis and Psychosis". The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923–1925): The Ego and the Id and Other Works, 147-154

- Gay, Peter (ed., 1989), The Freud Reader. W.W. Norton.

- Rangjung Dorje (root text): Venerable Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche (commentary), Peter Roberts (translator) (2001)Transcending Ego: Distinguishing Consciousness from Wisdom, (Wylie: rnam shes ye shes ‘byed pa)

- Kurt R. Eissler: The effect of the structure of the ego on psychoanalytic technique (1953) / republished by Psychomedia

External links

- American Psychological Association

- Sigmund Freud and the Freud Archives

- Section 5: Freud's Structural and Topographical Model, Chapter 3: Personality Development Psychology 101.

- An introduction to psychology: Measuring the unmeasurable

- Splash26, Lacanian Ink

- Sigmund Freud

- Sigmund Freud's theory (Russian)